Monumental Church:

A Small Site With a BIG Place

in Our Nation’s History

Welcome!

Today, on this site, you see a church; but it was not always so.

Sections:

Powhatan Land

Virginia Ratifying Convention

The First Theatre

Richmond Theatre

Richmond Theatre Fire

Gilbert Hunt

Monumental Church

Historic Richmond's Restoration Work

Learn More: Architecture

Learn More: Links

Want to Tour Monumental?

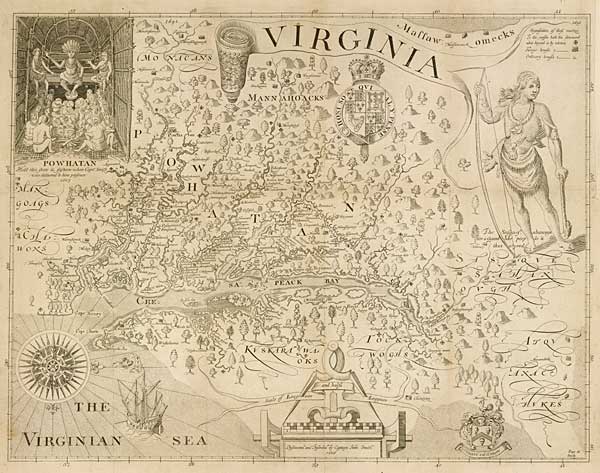

Powhatan Land

This site’s story begins on Powhatan land.

Library of Congress, Virginia (John Smith, 1624)

In 1607, when the English arrived, the area was controlled by the Powhatan tribe who resided in a village on a hill above overlooking the river (likely today's Fulton Hill).

By the mid-1600s, this site was under the control of English colonists. William Byrd I acquired much of the land that is downtown Richmond in 1678 and his son founded Richmond, commissioning William Mayo to survey the town in 1737.

In 1780, Virginia’s state capital was moved to Richmond (from Williamsburg) during the Revolutionary War. Then-Governor, Thomas Jefferson, did so because Richmond’s location was centralized and more easily defendable. Yet one year later, Richmond was burned to the ground by British troops under Benedict Arnold’s command. Within two years Richmond had recovered and rebuilt, but was still a small, growing city. By the first census in 1790 there were about 4,000 residents, about 40% of them enslaved.

Infrastructure in Richmond then was new. Richmond had just grown from a town to a city, had just become the state capital, had just burned to the ground by the British, then just had been rebuilt!

This site, the future home of Monumental Church, was already a gathering place for Richmond. Chevalier Quesnay de Beaurepaire, a French officer in the Revolutionary War, originally proposed that this site be an esteemed square to house the first Academy of Fine Arts and Sciences on the continent (known as “The Theatre Square”); this plan was jettisoned during the Revolutionary War. But that original earlier vision influenced the site’s iteration as home to the first Richmond Theatre, which opened in 1786.

By the late 1780s, the new infrastructure of state Government was just steps away with the Capitol and surrounding area being completed.

Virginia Ratifying Convention

It was on this site that the Virginia Ratifying Convention was held for three weeks in June, 1788.

Why is this important? Because the decisions and debates there affected the final form of our United States Constitution.

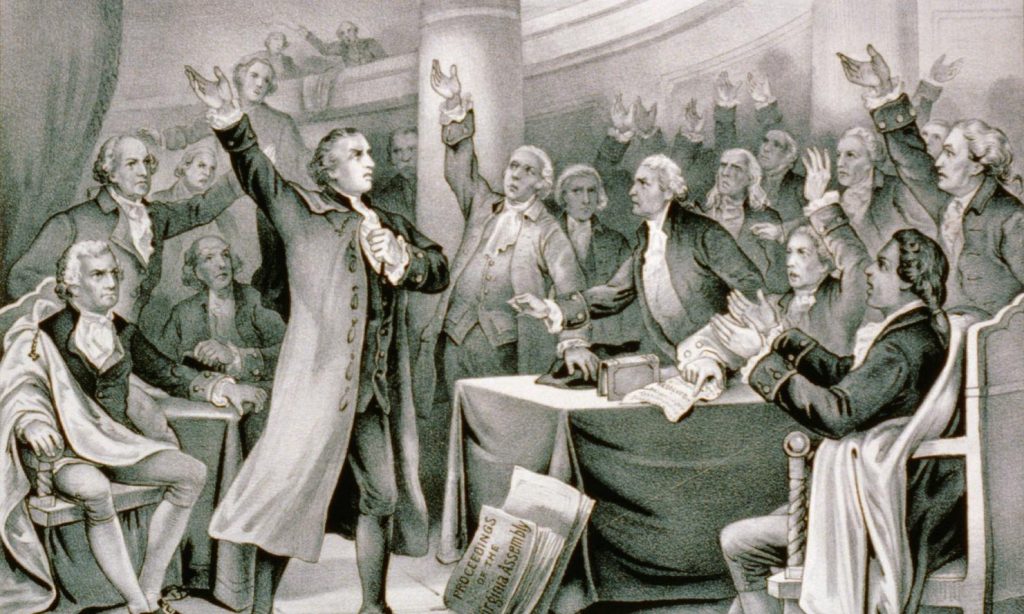

Delegates to the convention included Edmund Pendleton, Edmund Randolph, George Wythe, Light Horse Harry Lee, John Marshall, George Mason, and James Monroe. Patrick Henry, the leader of the opposition, objected to the consolidation of power in a federal government at the expense of the states. James Madison led the delegates supporting adoption of the constitution.

Patrick Henry delivering his “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” speech in 1775. Currier & Ives, c1876/Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. (neg. no. LC-USZC2-2452)

Wait! In that picture, Patrick Henry isn’t arguing in Monumental Church!

Correct, Monumental Church did not yet exist! While this painting portrays Patrick Henry famously arguing against tyranny in his famous "Give Me Liberty Or Give Me Death" speech given at Historic St. John's Church in Richmond in 1775, he also later argued against strong centralized government during the Virginia Ratifying Convention, which met on this site from June 3-27, 1788. Unfortunately, neither photography nor Instagram existed to capture these moments! Few paintings depict those historic days, but this one aptly illustrates Mr. Henry’s fiery speeches.

We see that Patrick Henry can argue. What exactly did he say? Read his words, here!

Also known as the Virginia Federal Convention, the Virginia Ratifying Convention was an open-to-the-public debate held in the Richmond Academy, which then stood on the site.

Crowds gathered. Newspapers here and abroad published headline after headline as Virginia leaders argued over the roles and powers of federal government, the states and the people, taxes, slavery, the rights of the people that should be protected, and whether union was better than disunion. Read the debate over slavery in their own words here.

At the Virginia Ratifying Convention, about 40 amendments were recommended. Many of the recommendations made were later incorporated into our nation’s final Constitution, into the Bill of Rights!

Years passed.

The First Richmond Theatre

Now only 12 years old, the first Richmond Theater, a wooden barn-like structure, was destroyed by fire in 1798.

Fast forward a few years…

The Richmond Theatre

Richmond continued to grow, and so a better, bigger theater was constructed of brick: The Richmond Theatre, built in 1806.

Few, if any, places tell us more about ourselves as a community than Monumental Church. Few, if any, have a more important story to tell to future generations than this National Historic Landmark.

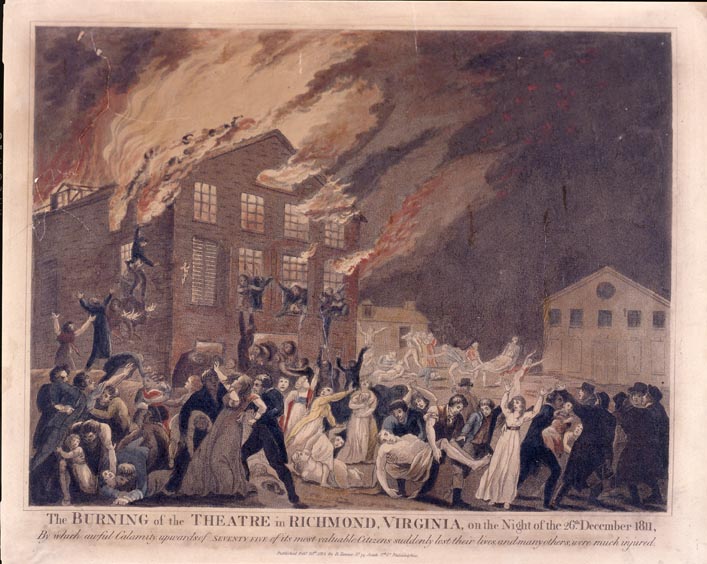

The Richmond Theatre Fire

PGA - Tanner--Burning of the theatre... (B size) [P&P], Library of Congress, 2003689321, digital id pga 08414 //hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pga.08414.

When the initial sparks fell on the stage, the audience thought it was lighting effects. However, the scenery quickly began to burn and the fire spread rapidly. An actor yelled “the house is on fire!” and panic began. Everyone rushed to get out of the burning building as the fire intensified and the theater filled with thick black smoke. Those on the stage and in the gallery had their own exits. Those sitting in the boxes had a single exit through narrow passages and a single stairway, that quickly collapsed under the weight of the evacuating people.

Official records identified 72 people who perished in the chaos and conflagration. Men, women, children, Black, white, free and enslaved were there. It was a catastrophic event that affected almost everyone in Richmond and it was the deadliest urban disaster in the United States to have occurred at that time in history.

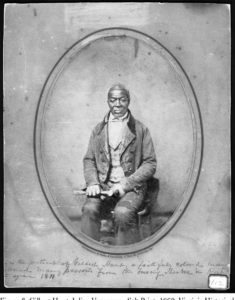

Gilbert Hunt

Gilbert Hunt. Julian Vannerson, Salt Print, 1860, Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, Virginia.

But with the horror of those who perished also came tales of heroism – most notably of those saved by the enslaved blacksmith Gilbert Hunt and Dr. James D. McCaw. Hunt found a ladder and placed it against the wall, while McCaw smashed through a second floor window and teamed up with Hunt to save a dozen women before jumping himself. Hunt then dragged McCaw to safety, creating splints for McCaw’s mangled leg and binding his wounds.

Gilbert Hunt led a remarkable life— learn more here.

Monumental Church

On December 27 of that year, the city purchased the site of the old theater to create a perpetual memorial to the victims. While many important and prominent citizens died in the blaze, the victims represent a wide cross-section of society. From governor to student, young and old, the fire killed indiscriminately and in a final gesture of humanity, all but one are interred together in a crypt built on the ashes of the Richmond Theatre.

Chief Justice John Marshall was named to chair a committee to create a suitable monument above the grave.

Completed in 1814, Monumental was designed by architect Robert Mills of South Carolina, best known for designing the Washington Monument and Thomas Jefferson’s only architectural pupil. Monumental remains one of the earliest and best examples of Greek Revival architecture in the United States, and is one of the first American monuments to incorporate Egyptian motifs. Within Richmond, Monumental Church’s architectural significance is considered second only to the Virginia State Capitol. Today, Monumental is the only surviving example of the five domed churches that Mills designed.

Monumental Church is architecturally, historically and culturally significant as a site that connects us to our past and defines who we are as Americans, as Virginians, and as Richmonders.

Monumental Church, a National Historic Landmark, served as an Episcopal Church from 1814 until its deconsecration in 1965.

Historic Richmond's Restoration Work

In 1983, Historic Richmond acquired Monumental Church and has worked diligently to preserve and restore Monumental Church as one of Richmond’s premier architectural landmarks. Historic Richmond continues to maintain this unique place as a nondenominational, deconsecrated space ideal for group events, educational programs and historic tours.

Monumental has been restored to its 1814 period of significance.

Historic Richmond’s restoration began with addressing the issues to “seal the building envelope” with repairs to the roof, gutters, limestone, stucco, mineral paint, stone repair, columns, doors, windows; mechanical and electrical upgrades; interior paint and plaster repairs; beautifully rendered “marbleizing” of the altar, and faux graining of the sanctuary doors in accordance with precise paint analysis; construction of an outdoor terrace and lighting; repair of the historic iron fence; restoration of wood and tile floors; and replication of the historic marble monument.

Many Richmonders have contributed to our efforts. A few are named on our patio, where we also have included a timeline.

See the latest updates on our restoration project, here!

Learn More: Architecture

Design Details

The original design that Robert Mills submitted for Monumental Church was “avant-guard.”

Its design is true synthesis of ideas from Jefferson and Latrobe.

- The sanctuary was octagonal with a Delorme dome.

- A steeple was originally planned to top the tower at the rear of the church, but was never built due to lack of funding.

- The traditional entrances to the church were through the east and west porticos. The front door was not used as an entrance. Mills intended the front door to be seen from the front portico as a door to a tomb, reminiscent of a Roman tomb. As such, the tradition was to open the front door only once a year at Easter. Years later the front door became the main entrance.

- Side porticos have beautiful double staircases that are masterpieces of design and construction.

- Monumental’s auditorium style reflects the emphasis placed on “preaching and teaching.” All eyes were focused on the preacher.

Materials

Aquia sandstone from Aquia Creek in Northern Virginia was used for the front portico, the same stone used for the White House. And, like the White House, the stone was painted white with a lime wash.

The rest of the structure is stucco over brick.

Delorme Dome

Robert Mills learned this dome building technique from Thomas Jefferson. It is called a Delorme (or de l’Orme) dome and is constructed of wood. This technique allows for a large impressive dome to be built relatively inexpensively and quickly. Monticello is another well known example of this technique.

Mills designed five auditorium-style domed churches like Monumental Church. One was built in Charleston, S.C., one in Baltimore and two in Philadelphia. Monumental Church is the only one still standing.

Pulpit

The pulpit is illuminated by a hidden skylight known as a lumière mystérieuse. This hidden window produces a special effect of throwing downlight over the speaker, much like modern stage lighting lights an actor on stage.

The acoustics are intended to project sound from the pulpit.

The original pulpit was removed (and restored by The Valentine Museum).

The vivid blue marbleized altar was based on precise paint analysis to match the original color scheme.

Symbolism

Symbols of mourning can be seen on both the interior and exterior of the church.

- Pulpit Capitals:

- Upside down torches = life extinguished or snuffed out

- Stars = heaven and eternity, referencing the Christian belief in life after death

- Drapery = funeral drapery, burial shroud or catafalque

- Laurel (on sides) = victory and symbol of eternity

- Balcony Capitals:

- Capped with sarcophagus-shapes

- “Menorah” shaped item found above the capitals is a unique Mills design.

- Doorways/Windows: The sarcophagus shape is also seen over each doorway and window, both interior and exterior.

- See “The Front Portico and Monument” below for exterior symbols.

Pews

The pews on the main floor are original, but the high backs have been cut down to a lower height.

Several of the pews have family plaques. In order to raise the money to build the church, pews were sold. Richmond families bought all the pews and enough money was raised to build the church. Most gave $200.

John Marshall bought a pew for $390. Legend has it that to be comfortable he used to open the pew door and stretched his feet out in the aisle.

The seats in the balcony were free. Those who could not afford pews and enslaved members of the congregation sat there.

The pew in which Edgar Allan Poe sat with his foster parents is near the East Stairwell.

The Front Portico and Monument

The Front Portico was inspired by the Greek Temple of Apollo at Delos. The unfinished nature of the columns (only partially fluted) may reference the unfinished lives of the fire victims.

The Front Portico was inspired by the Greek Temple of Apollo at Delos. The unfinished nature of the columns (only partially fluted) may reference the unfinished lives of the fire victims.

The monument, carved from marble, combines a sarcophagic base topped with a funerary urn. The names of the victims are carved into the walls of the sarcophagus, and its cavetto cornice is decorated with a winged sun disk, a symbol of Ra (the sun god in Egyptian mythology). Ra was believed by the Egyptians to have healing in his wings.

- Architect Robert Mills understood the Egyptian tradition of honoring the dead in powerful and permanent forms, and his use of Egyptian elements in the design is evidence of his admiration for the buildings of antiquity.

- It has been speculated that this is one of the first American monuments to incorporate Egyptian motifs.

- The name of each and every fire victim is engraved on the monument. The names of the male victims are on the south side (facing Broad Street). The names of the female victims and children are on the remaining three sides. The names of the enslaved victims appear on the base.

- Frieze around the front portico: These urns are tear vials (lachrymatory urns) from the ancient Greek tradition of collecting tears shed during mourning to honor the dead.

The marble urn is adorned with funerary symbols:

- Upside-down torches = end of life or life extinguished

- Winged hourglasses = how fleeting our time on earth is (tempus fugit)

- Wreath of cypress branches = mourning

- Finial topping the urn is an eternal flame = immortality

Replication of the Monument

In 1999, irreparable damage to the monument (resulting from decades of exposure to pollutants) was first revealed, when the funerary urn capping the memorial toppled to the ground. A conservation study concluded that damage was too extensive for conventional restoration techniques to work. The only viable choice was to dismantle the original monument and replace it with a replica.

The replication process took over three years to complete, and became an international effort involving artisans, scientists, preservationists, and conservationists. Cutting edge laser technology (3-D scanning) was used to create the replica.

The monument replica was sculpted in Ireland by the same company that created the Princess Diana Memorial in London’s Hyde Park.

It was carved from Greek Thasos marble and installed in September 2005.

Historic Designations

- National Historic Landmark (since 1971)

- National Register of Historic Places (since 1969)

- Virginia Landmarks Register (since 1968)

Learn More: Links

Below are a few of our staff picks for learning about this site. Be aware of the difference between primary and secondary sources, of academic references vs. storytelling, and how writing from one perspective can still reveal testimony of another.

Origins

- Dabney, Virginius. Virginia: the New Dominion. 1971. ISBN978-0-8139-1015-4

- https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/first-anglo-powhatan-war-1609-1614/

- https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/richmond-during-revolutionary-war

- https://virginiahistory.org/learn/historical-book/chapter/invented-scenes-narratives

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/659023#metadata_info_tab_contents

- 1790 Census (page 10)

- Black-White Relations in Richmond, Virginia, 1782-1820

- https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/first-anglo-powhatan-war-1609-1614/#:~:text=In%201608%2C%20Powhatan's%20men%20ambushed,latter%20group%20into%20Piankatank%20territory.

- https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/chronology-of-powhatan-indian-activity.htm#:~:text=The%20Powhatan%20Indian%20lands%20encompassed,100%20miles%20by%20100%20miles.

Virginia Ratifying Convention

- Grigsby, Hugh Blair (1890). Brock, R.A. (ed.). The History of the Virginia Federal Convention of 1788 With Some Account of the Eminent Virginians of that Era who were Members of the Body. Collections of the Virginia Historical Society. New Series. Volume IX. Vol. 1.

- Kaminsky, John P. (1988–1993). The Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution: Ratification of the Constitution by the States. Vol. 8–10

- Maier, Pauline. Ratification: the people debate the Constitution, 1778–1788, 2010, ISBN978-0-6848-6855-4

Richmond Theatre Fire and Monumental Church

- Baker, Meredith Henne. The Richmond Theater Fire: Early America's First Great Disaster. LSU Press, March 2012.

- Shockley, Martin Staples, The Richmond Theatre, 1780-1790

- https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/fire-richmond-theatre-1811/

- https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/va1448/

- https://theshockoeexaminer.blogspot.com/2018/03/hero-hidden-in-hindsight-gilbert-hunt.html

- Gilbert Hunt, the City Blacksmith https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/gilbert-hunt-the-city-blacksmith-by-philip-barrett-1859

- REMARKS ON THE THEATRE, AND ON THE LATE FIRE AT RICHMOND, IN VIRGINIA. LC York: Printed by Thomas Wilson and Son, for the Author; AND SOLD BY WILLIAM ALEXANDER, YORK; ALSO BY DARTON, HARVEY AND DARTON, GRACECHURCHSTREET, AND WILLIAM PHILLIPS, LONDON; AND BY M. M. AND E. WEBB, CASTERSTREET, BRISTOL. 1812.

- [Cut] Theatre on fire. Awful calamity! A letter from Richmond, Virginia dated Dec. 27, says "Last night the theatre took fire and was consumed, together withe about 8- people, with the governor Smith- many were trampled to death under foot, 1812.

- Calamity at Richmond, being a narrative of the affecting circumstances attending the awful conflagration of the theatre in the city of Richmond, on the night of Thursday, the 26th of December, 1811. By which, more than seventy of its valuable citizens suddenly lost their lives, and many others were greatly injured and maimed. Collected from various letters, publications, and official reports, and accompanied with a preface, containing appropriate reflections, calculated to awaken the attention of the public, to the frequency of the destruction of theatrical edifices. Miscellaneous Pamphlet Collection (Library of Congress)Philadelphia, Published and Sold by John F. Watson, 1812.

- Fisher, George D. History and Reminiscences of the Monumental Church, Richmond, Virginia, from 1814 to 1878. Richmond: Whittet & Shepperson, 1880.

- https://www.classicist.org/articles/classical-comments-monumental-church/

- https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/VLR_to_transfer/PDFNoms/127-0012_Monumental_Church_1969_Final_Nomination_NHL.pdf

Want to Tour Monumental?

We'd love to share the site of the Richmond Theatre Fire, Virginia Ratifying Convention, and more with you. Click here to learn more about tours.